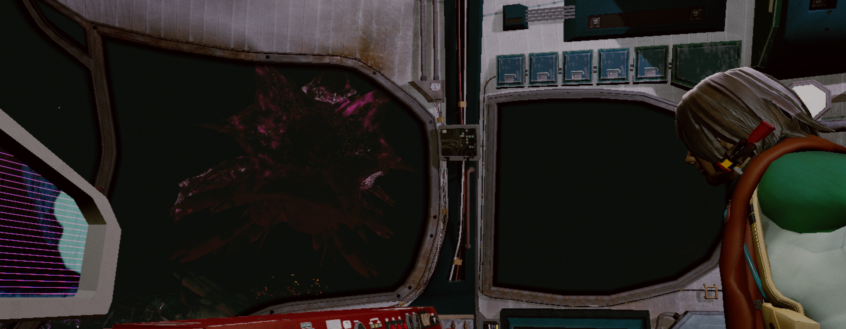

Baby Levi attacking the Pravarthak

Making Max Q as a VR film has had a ton of challenges. Many of them technical (still seems to be no way for us to render a 360 video with Unreal Engine 4.26 using the Post Processing materials we need for the water surface and underwater world!), but just as frustrating, many of them are creative / artistic.

There have been three key things that I (this is Joel, here, director) have found.

1) Eyelines – making sure the viewer knows where to look so they don’t miss the important stuff, but still allowing them the sense of freedom of choice.

2) Communicating to non-VR viewers the sense of awe and wonder that is inherent in watching something with the headset! Even making these blog posts, I feel disappointed with the way the images look on the flat screen. Watching in VR (as many have luckily told me after seeing the film with the HMD) is SOOO different than watching it on a monitor.

3) The sense of scale is sometimes challenging to convey, even with the headset on.

Directing the Eye

The first challenge (eyelines) was easiest for me to understand. As an animator, I think and talk a lot about making sure the audience is looking in the right place. Because we’re creating literally every pixel on the screen, we have to make sure the blocking and staging is spot on so nothing is missed.

Here’s a (large, apologies) GIF showing how some of this was done in the first part of the film. Mostly in this scene it’s done with movement – there are animated elements moving around the screen that are hopefully large and interesting enough that the viewer will want to watch them. They lead to the next thing the viewer is meant to see, then the next.

If the viewer does veer “off course,” there are interesting cross-lines to try to bring their attention back to the key points of interest.

A few years ago I was at a film festival (with another film, before I’d even considered starting a VR film) when I got into a discussion (or perhaps “argument”) about VR films with an old-school filmmaker, who I respect very much and whose work I like very much. I was surprised to hear him make the statement “VR filmmaking is not filmmaking. You’re just setting a camera in a space, not directing anything.” Paraphrasing, there, a bit. This is something I think about a lot, and it was probably a bit part of the reason I starting pondering VR as a medium. My response, which I believe even more, now, was that the truth is the opposite. It takes an even stronger director to make a VR film work. I absolutely will NOT say that I am that director, but it’s even MORE important to get the audience to see what you want them to see, all while letting them believe they’re simply looking at whatever they WANT to. We have to make them – with sound and light and movement – want to see what WE want them to.

Parts of Max Q are very directed, especially with movement, but other parts use sound and light to draw attention. There are still long portions of the film that let the viewer explore the space. Having the camera locked down made some of the other challenges, detailed below, even harder.

Inside the Desiderus – the levi mamma doesn’t look that big, even in the deep dark of the ocean where our minds fill in missing details

A sense of Scale

From inside the shuttle, from the VR viewer’s perspective, the sense of scale is simultaneously enhanced and diminished. All the tiny details in the ship suddenly come to life! The tiny wires on paneling, the flickering of the screens in the ship – all loom large. And yet, many things that are actually MASSIVE in the world can feel much smaller.

Some of this is due to the sci-fi nature of the film – we have no real way of knowing, ourselves, how big that alien rock is, or that weird leg-fish creature! There’s no “banana for scale”.

The leviathan mamma, for example – when seen first from inside the shuttle, it looks Big, but not really MASSIVE.

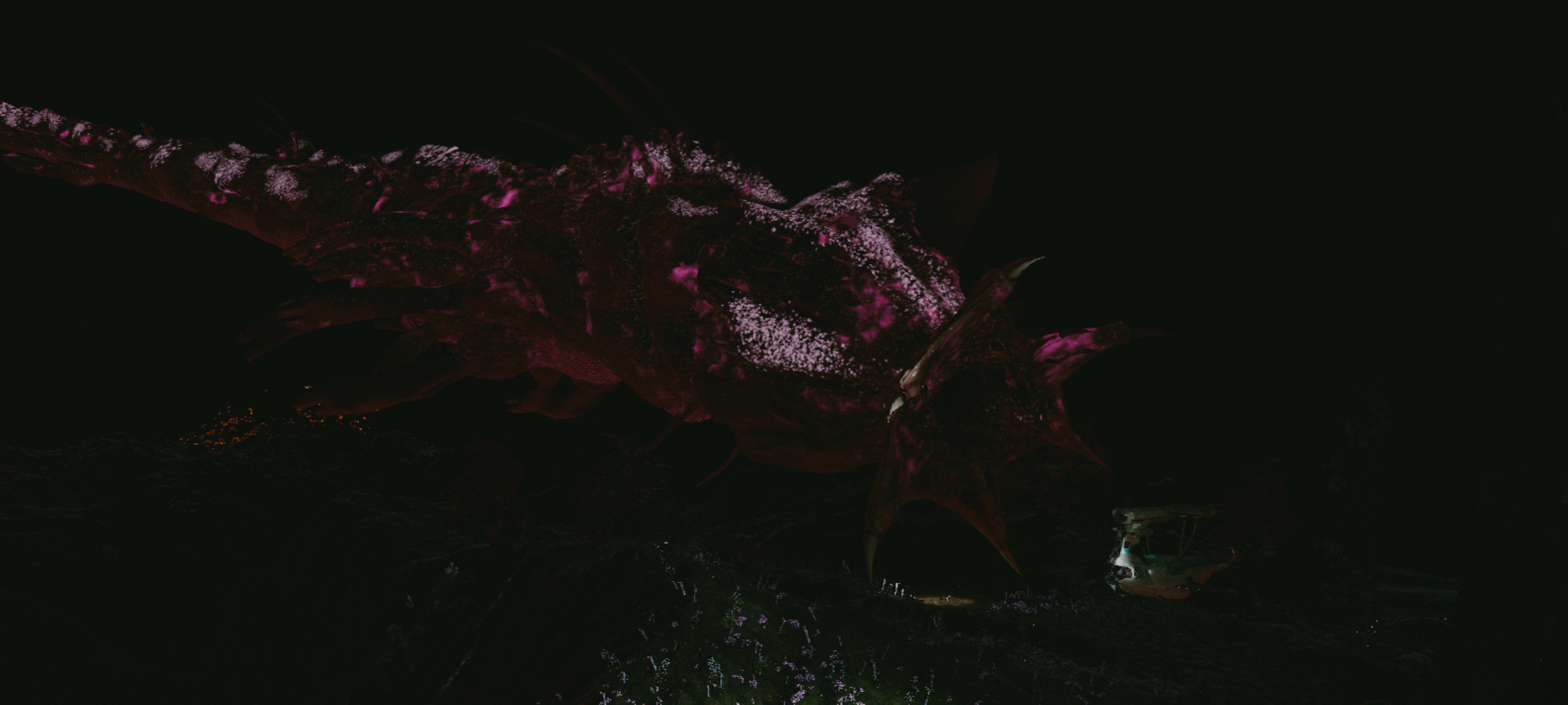

Levi from OUtside – oop! She’s really big!

Looking from OUTSIDE the shuttle, however, we can see that the scale is impressive and much more terrifying.

I’m honestly not sure what the solution is to this issue, other than to move the camera to a new vantage point. Unfortunately, this diminishes the efficacy of the immersion.

Immersive filmmaking

To me, the whole point of VR is to place viewers IN a situation. When we start also using film language, it becomes some in-between medium – not really film (because it’s so subjective) and also not best taking advantages of the immersion.

The majority of VR films that I’ve seen (NOT claiming to be expert, and have not by any means exhausted the filmography), especially animated films, are more experiential / experimental. It’s possible that films like “Dislocation” by Veljko and Milivoj Popović are best equipped to explore the strangeness that is VR cinema.

The “subjective camera”, where the audience sees the world through the eyes of a character, allows for us to experience the events directly from, creating the heightened sense of immersion. It’s less passive. We are truly present in the scene. However, working within VR presents unique challenges. Traditional cinematic language—like cuts, edits, and controlled framing—becomes (if not done well, which I fear would be the case were I to attempt it) less effective or even jarring in VR. Viewers have full control of where they look, and rapid cuts can disrupt the sense of presence, making it harder to guide attention and tell a coherent story.

I don’t think we’ve yet found it. It took us a while with Film to discover the language, I have hope we’ll get there with VR. Unfortunately, the potential audience is so small (with the hardware requirements being such a major barrier) that it may take us a while.

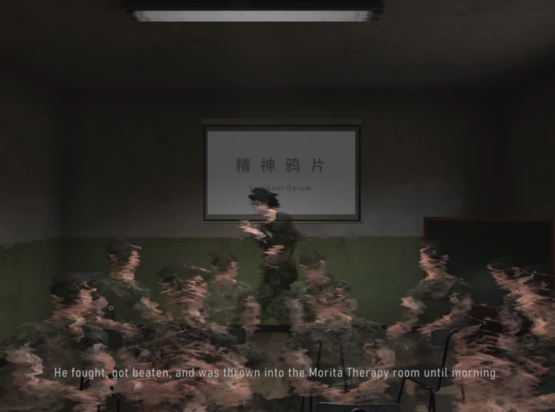

Dislocation, by

Dislocation, by

I also wonder if a lot of the lean towards experimental animation in VR is because there is so little interest (comparatively) in the medium. There’s no money to be made (too small a potential audience) so not much being invested in it. So because creators of this type of content frequently have little to no money, the focus of the projects becomes more about experience, story, and emotion vs polish and Hollywood-style production.

Diagnosia, by

The challenge for creators is to develop a new language of VR film that embraces this medium’s strengths—such as immersion and interactivity—while carefully adapting the pacing, movement, and transitions to respect the viewer’s freedom and maintain narrative clarity. Finding this balance is key to unlocking VR’s potential as a powerful storytelling tool. It is up to independent experimental animators to unlock the true potential of VR as a storytelling medium—not by making it “mainstream,” but by proving its artistic value and immersive depth. These creators are at the forefront of exploring VR’s ability to merge narrative, environment, and interaction in ways that traditional cinema can’t, crafting experiences that resonate deeply and redefine what it means to engage with a story. In doing so, they are not merely popularizing VR, but shaping it into a powerful tool for emotional and narrative exploration.

If another VR film is in my future, it will follow the leads of people like the Popovic’s, and films like “The West Flemish Pub Experience” by Joren Vandenbroucke, and “Diagnosia” by Zhang Mengtai.